Weighty Words

Last week, I received an email from John in North Carolina with the subject line "Love the tool, hate the metaphor":

Dear Professor Sword,

I enjoy reading your work and love using the Writer's Diet tool. However, I did want to share my extreme hesitation to use this with my classes. The idea of lean vs. flabby prose promotes a fat-phobic environment. I try to cultivate a place where writers of all sizes feel comfortable, including mentioning in class that the writer's diet is unnecessarily fattist. Have you ever considered updating the image with something more affirming or neutral?

I replied as I usually do, thanking John for taking the time to write and offering a few comments and suggestions:

The phrase "flabby or fit" is meant to refer to muscles, not to body types, and the overall message is a positive, health-focused one: If you want to develop strong muscles, it's best to eat a healthy diet and exercise regularly; likewise, if you want to develop strong sentences, you need build them up with good, nutritious words (not empty calories/clutter) and put them through a vigorous workout.

If, despite this explanation, you and your students still disapprove of the Diet and Fitness metaphor, you can use the blue Settings wheel to change the theme: for example, to Clear Skies ("cloudy or clear?"), Solid Ground ("swampy or solid?"), or Clean House ("cluttered or clear"?).

Ideally, the online Writer's Diet test should be used as a supplement to the book, not as a stand-alone tool. At the very least, I would encourage you and your students to spend some time reading my free online User Guide, which explains the key principles behind the test and offers lots of handy hints for getting the most from the tool.

Members of my WriteSPACE virtual writing community get access to a premium version of the Writer's Diet test that produces a customized Action Plan for every sample submitted -- using their preferred theme, of course! You can try out the Writer's Diet Plus tool by using the discount code WRITERSDIET to get your first month of membership for free.

But John's question got me thinking. What other metaphors for writing and editing do writers frequently employ, and which of these, like the Writer's Diet, might be open to ontological critique?

Cognitive load: If you attended my WriteSPACE Special Event last week with psycholinguist Steven Pinker, you'll have heard us talk about cognitive load, a phrase used by psychologists to describe the amount of working memory required by the brain to complete a given task. Long, difficult sentences -- those filled with abstract language, disciplinary jargon, parenthetical phrases, subordinate clauses, and the like -- place a heavy cognitive load on our readers, thereby sapping their mental energy and reducing their comprehension.

Left-branching vs. right-branching sentences: In an illuminating blog post titled How to Write a More Compelling Sentence, Inger Mewburn (aka the Thesis Whisperer) explains the difference between what linguists call "right-branching" versus "left-branching" sentences: right-branchers start with a subject-verb-object cluster and then add supplementary information, whereas left-branchers pile on all the extras before we even know what the sentence is about. Steven Pinker offers this example of a left-branching sentence, the subject of which, policymakers, does not appear until more than halfway through: "Because most existing studies have examined only a single stage of the supply chain, for example, productivity at the farm, or efficiency of agricultural markets, in isolation from the rest of the supply chain, policymakers have been unable to assess how problems identified at a single stage of the supply chain compare and interact with problems in the rest of the supply chain." (Steven Pinker, The Sense of Style: The Thinking Person's Guide to Writing in the 21st Century).

The Lard Factor: In his book Revising Prose, Richard Lanham encourages writers to calculate the Lard Factor of an edited piece of prose by subtracting the number of words in the edited sentence from the number of words in the original, then dividing the difference by the original. For example, if we were to trim the 63-word behemoth quoted above down to 43 words, the Lard Factor (or percentage of excess words eliminated) would be 32%.

Viewed through a certain kind of critical lens, all of these metaphors are problematic. Cognitive load suggests that light is good, heavy is bad. The branching sentences metaphor depicts right as good and left as bad (a sinister sign of an implicit bias against left-handed people?) Lanham's Lard Factor exercise labels lean as good and fatty as bad (another "fattist" metaphor?)

Yet each of these metaphors also reflects a physical reality. Heavy loads are harder to lift than light ones; the English-speaking brain favors sentences that read, like words on the page, from left to right; lean meat is healthier to eat than fatty meat (unless you're a vegetarian, in which case you probably find the entire Lard Factor metaphor deeply unappealing).

Metaphors can shape us or empower us, lift us up or let us down. Arthur Quiller-Couch infamously urged writers to murder your darlings -- that is, to commit infanticide against your most cherished sentences. But we don't need to succumb to that kind of self-punitive advice; nor should we confuse a healthy diet of well-chosen words with an anxiety-inducing starvation diet. Editing can be a joyful act, with affirmational metaphors to match.

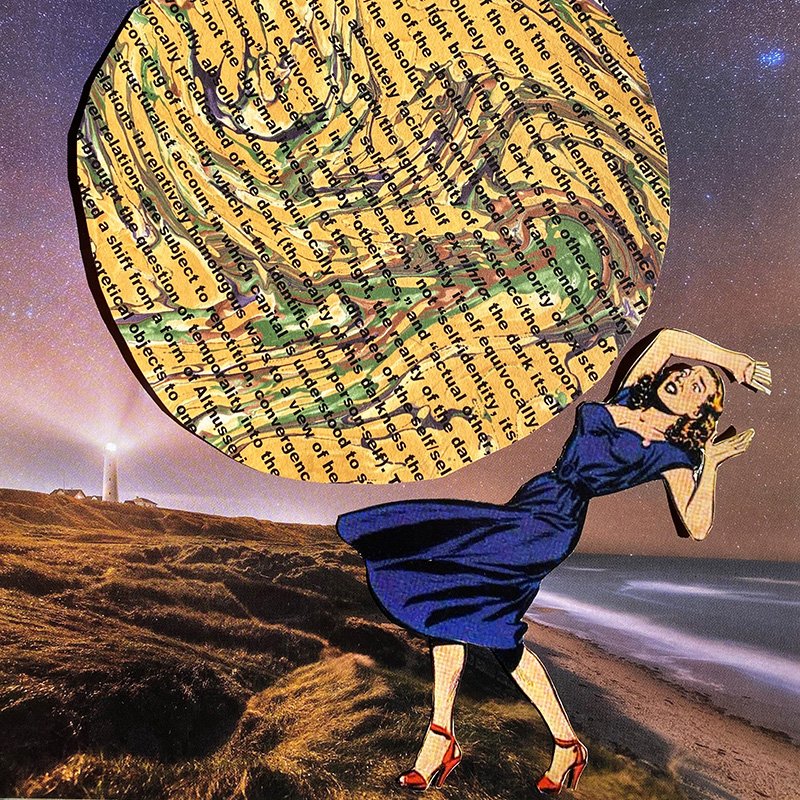

That woman about to be crushed by weighty words? Take another look. Maybe that falling boulder is a beachball filled with air, and she's playing beach volleyball!

Subscribe here to Helen’s Word on Substack to access the full Substack archive and receive weekly subscriber-only newsletters (USD $5/month or $50/year).

WriteSPACE members enjoy a complimentary subscription to Helen’s Word as part of their membership plan (USD $15/month or $150/year). Not a member? Join the WriteSPACE now and get your first 30 days free.