On October 17, I invited criminologist David R. Goyes, a senior researcher at the University of Oslo, to join me for a lively conversation on "Writing and Risktaking".

In the first hour of this free WriteSPACE Special Event, David and I discussed the benefits and (of course!) the risks of defying disciplinary conventions to produce bold, engaging academic prose. David recounted his own journey into a more stylish way of writing and shared some examples of pushback and (mostly) praise from co-authors, editors, and readers. In the second hour, we co-led a hands-on discussion and workshop for WriteSPACE members, guiding participants through some risky writing experiments of their own.

Here’s WriteSPACE Event Manager Amy Lewis’ personal account of the live event:

……………

This Special Event featuring Helen Sword and David Goyes offered a provocative entry into the world of risky writing. Breaking free from the straitjacket of academic prose is by no means an easy task; it takes a lot of courage to dismantle imitative writing habits, broaden your mindset, find supportive colleagues to back your ideas, and stand firm about the creative elements into your academic work.

Seems like a lot of obstacles, doesn’t it? But by the end of the session, Helen and David had convinced me of the great opportunities and joy to be found in risky writing.

Some memorable quotes from David in response to Helen’s questions:

Q: What is risky writing?

A: Risky writing could be going against the stream, challenging conventions, or using tools that others don’t use. It is risky because you think, ‘If I deviate from the academic standard, I won’t be published, I’ll be criticised, or I won’t be taken seriously.’

Q: Is it harder to take risks when you’re not a native English speaker?

A: Writing in your second language can make you a better writer. It’s risky, but it challenges you to achieve clarity and depth.

Q: Doesn’t risky writing lead to pushback from editors and peer reviewers?

A: It’s a myth! I would say that 95% of peer reviewers appreciate risky or creative elements. More often, it is the co-authors who generate pushback, or maybe it is even self-disciplining.

David and Helen spoke about imitative writing: Are we learning bad habits from our colleagues? It’s not uncommon for early-career scholars or academics in highly conventional fields to find themselves trying to imitate the writing style of their disciplinary canon. Early-career academics can also be the strictest peer reviewers because they feel the need to reproduce the harsh comments they received for their own first publications. It’s easy to feel trapped into thinking “This is how academic writing is done. I must speak and write in a certain way, and teach others to do the same.” A vicious circle indeed, and an unnecessary one.

What are some ways to break the cycle, you ask? Here are three common routes:

Social influence: Seek out likeminded risktakers and creatives in or beyond your discipline.

A crisis: Something just isn’t working, so you have to drastically devise a plan B.

Education: When you read a book or attend a course taught by an expert in the field, you’re exposed to new ideas that in turn encourage self-reflection (“Is this really the only way to do it?”). By reading this article, you are already well on your way towards becoming more aware of and empowered by risktaking!

(For more on how imitative behaviour molds culture, Helen recommends Culture and the Evolutionary Process by Robert Boyd and Peter J. Richerson).

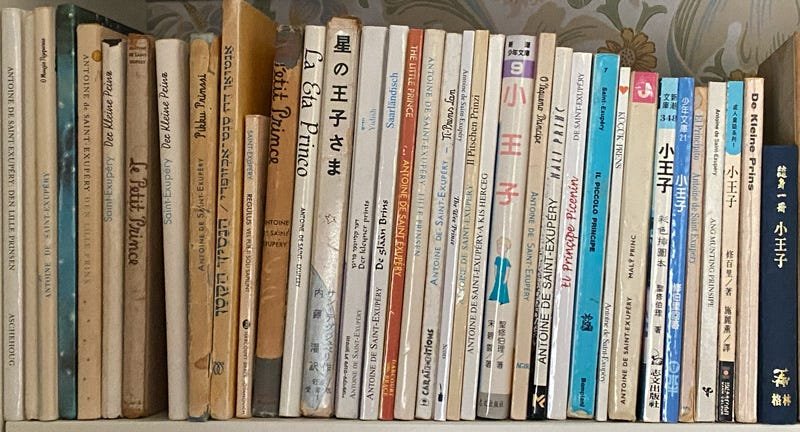

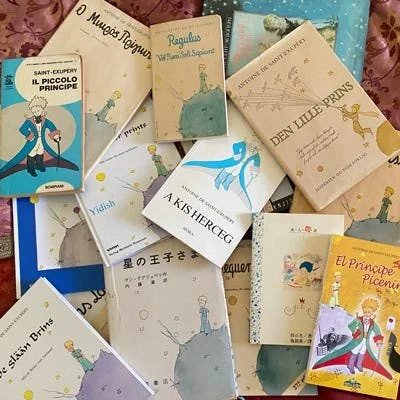

David showed us praise-filled reviews for his “riskiest” articles, which draw on techniques such storytelling, poetry, personal narrative, conversation, dialogue, and melodrama. Check out these articles by David and colleague for some excellent examples of risky writing that paid off:

For storytelling, see the introduction ‘Sour Milk’ of Goyes et al., “‘An incorporeal disease’: COVID-19, social trauma and health injustice in four Colombian Indigenous communities”, Sociol Rev, 71:1 (2023): 105–25.

For personal narrative, read David’s own dream research log in Goyes & Mari Todd-Kvam, “Dreams and Nightmares: Interviewing research participants who have experienced psychological trauma”, in Ethical Dilemmas in International Criminological Research (Routledge, 2023).

For dialogue, listen to interviewees’ personal voices and singing in Goyes & Sveinung Sandberg, “The soundtrack of criminal careers: On music, life courses and life stories,” Theoretical Criminology, 0:0 (2023).

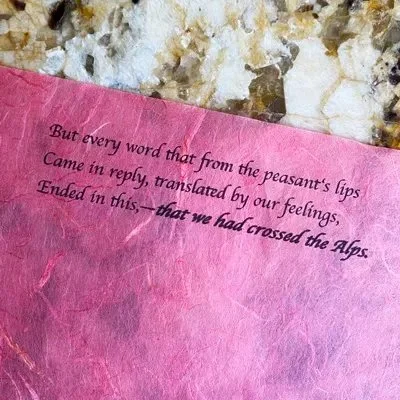

For poetry, see the ending of Goyes, “Latin American green criminology,” Justice, Power and Resistance, 6:1 (2023): 90-107.

David posed us a challenge: We must look at risk with new eyes. Something may be safe despite looking unsafe. He remembers going to a prison in Bolivia to conduct research; nervous about entering a high-security prison to interview murderers and other serious offenders, David was surprised when his scariest interviewee started crying and confessing his loneliness. We often erect boundaries and suffer from fears that have been taught to us or reinforced by others in our discipline. Unless we learn to push against these boundaries and scrutinise these fears, we can end up locking ourselves in our own kind of prison, a space where there is no creative licence to be found.

*************

In the second hour of the event — the workshop for WriteSPACE members — we delved into practical problems faced by academic writers. David provided his insightful expertise as an academic who has received both negative and glowing responses for his “risky” (aka stylish and creative) academic articles and discussed how to respond to negative feedback while remaining firm on your ideas.

As one participant noted in the comments:

Academia is, subtly perhaps, a very hierarchical environment. I'm grappling with how to establish myself and push the conventions of writing while ensuring I am taken seriously at the same time, despite being an early career academic.

To address some of the questions raised in the first hour, Helen and David guided us through several creative experiments, which I would encourage you to try right now. Grab yourself a pen and notebook and find a comfy space to do some freewriting:

5-min Prompt: Think about your current project. How can you bring risky writing into your work? Perhaps you might consider some of the following: Story, poetry, personal narrative, conversation, dialogue, melodrama…

5-minute prompt: Imagine Reviewer #2 (the grumpiest or most conservative gatekeeper you can imagine) responding to your risky writing. What do they say about it (and you)?

5-minute prompt: Now imagine Reviewer #1 responding positively and with high praise to your risky writing. What do they say about it (and you)?

For some of Helen’s articles that encourage risktaking in academia, see:

Sword, The First Person. Teaching and Learning Inquiry 7:1 (2019): 182-190. Republished in the Good Writing Gazette, 2020.

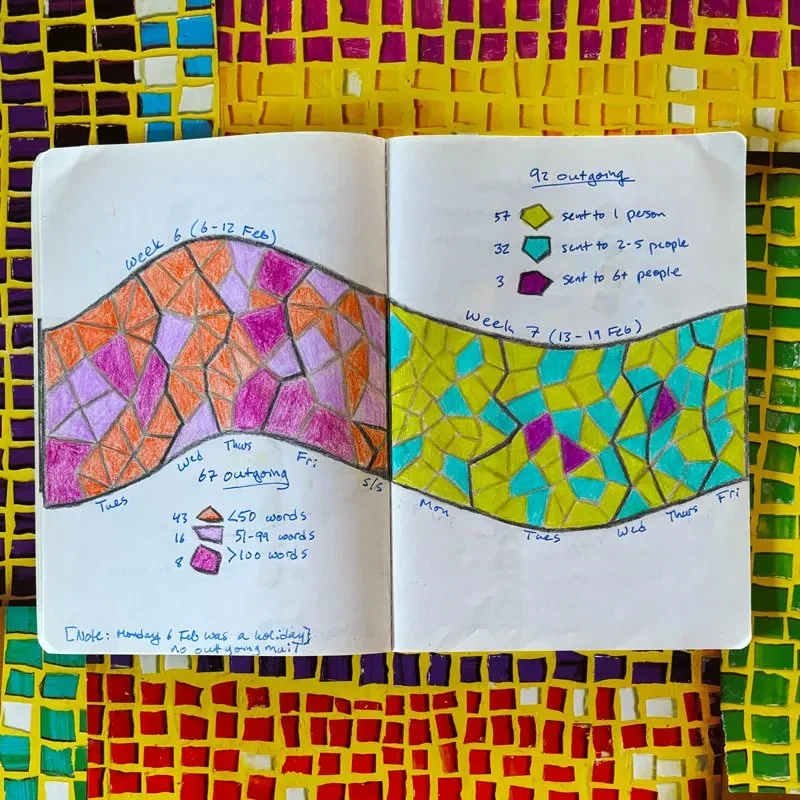

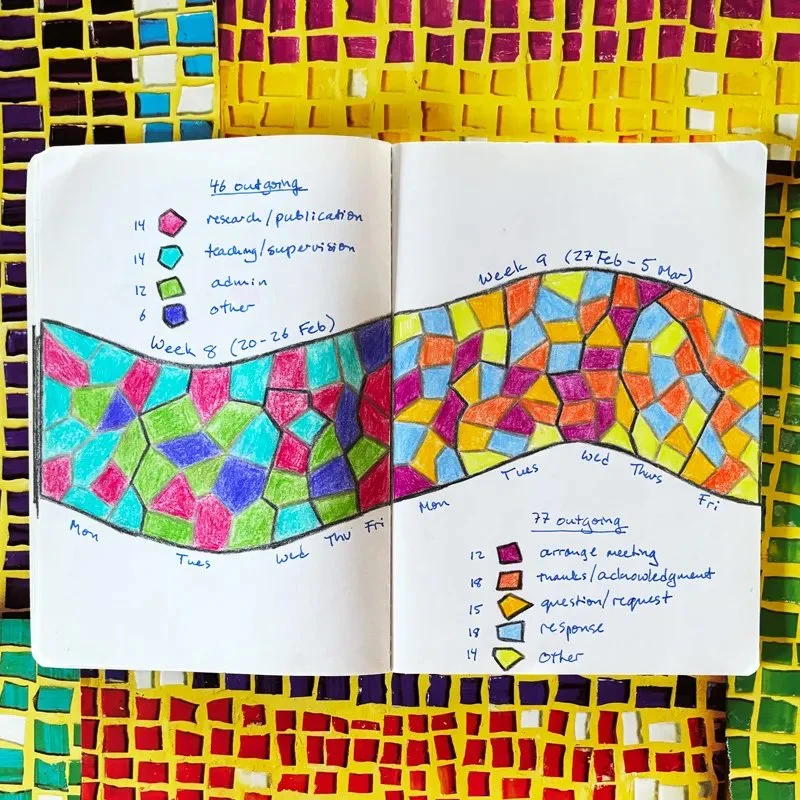

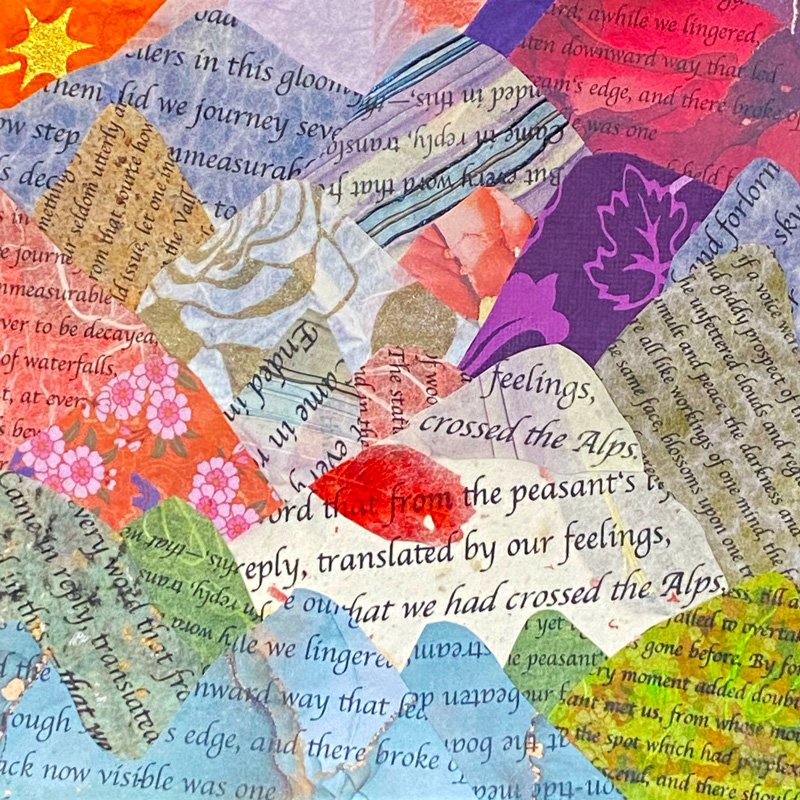

Sword, Snowflakes, Splinters, and Cobblestones: Metaphors for Writing, in S. Farquhar and E. Fitzpatrick (Eds.), Narrative and Metaphor: Innovative Methodologies and Practice (pp. 39-55). Singapore: Springer, 2019.

Sword, Marion Blumenstein, Alistair Kwan, Louisa Shen & Evija Trofimova, “Seven Ways of Looking at a Data Set,” Qualitative Inquiry, 27:4 (2018): 499-508.

Sword, “Seven Secrets of Stylish Academic Writing,” The Conversation, 13 July 2012.

A big thank you to David and Helen for this interesting and inspiring Special Event, and thank you to all the participants for sharing your comments and engaging questions.

See you again at the next event!