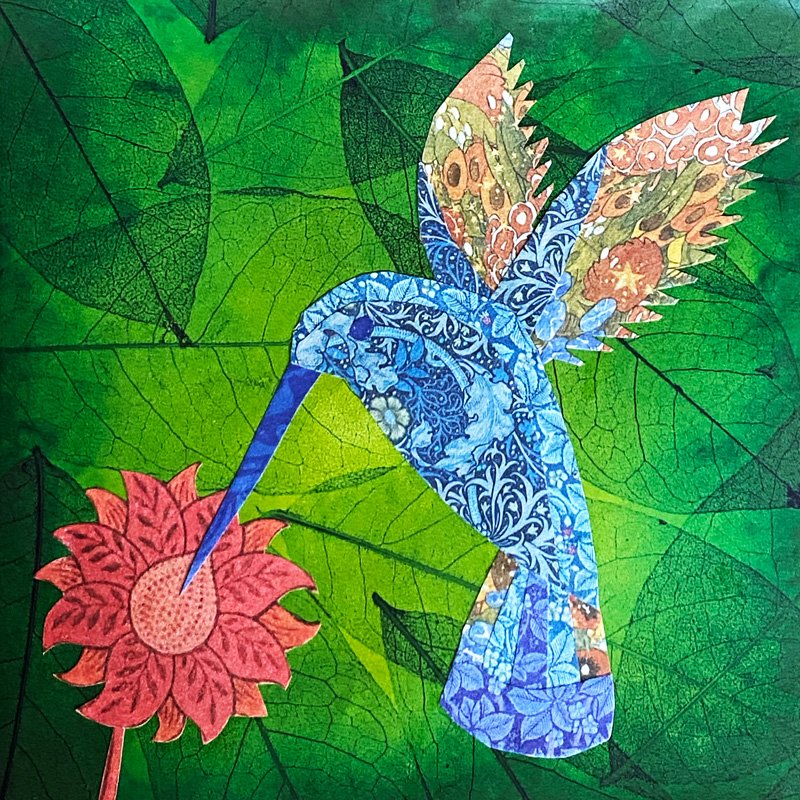

If you subscribed to #AcWriMoments — the 30-day series of daily writing prompts that I co-curated last month with Margy Thomas— you may recognize this image, which I’ve based on the gorgeous photograph of a yellow weaverbird building its nest provided by Steven Pinker as part of his Day 15 prompt, “Linger over good writing.”

Lingering over good writing (and encouraging other writers to do the same) is pretty much what I do for a living — so what better way to illustrate the technique than by lingering over Steve’s own #AcWriMoments contribution?

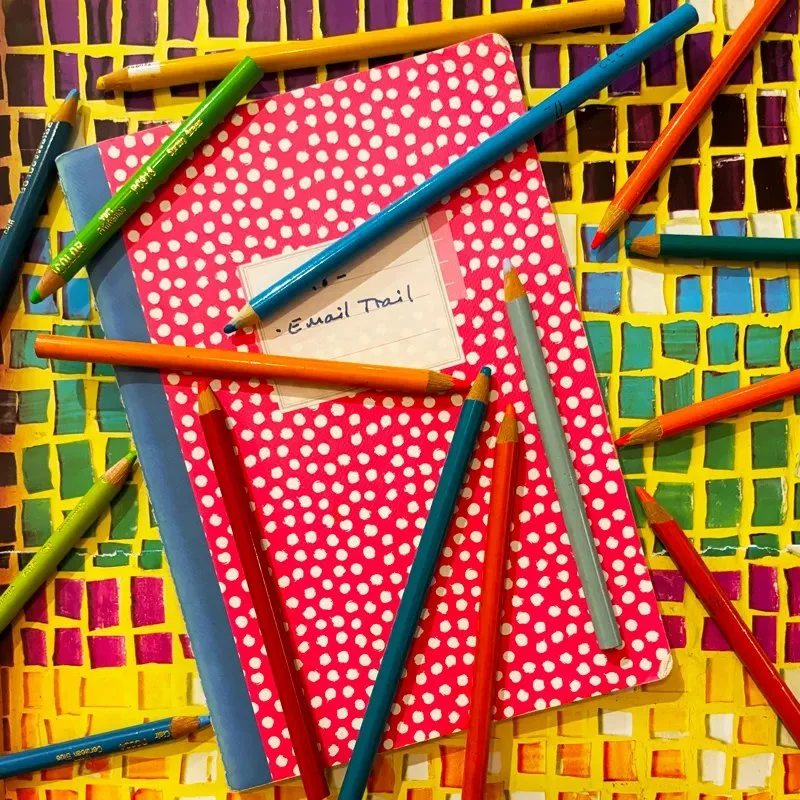

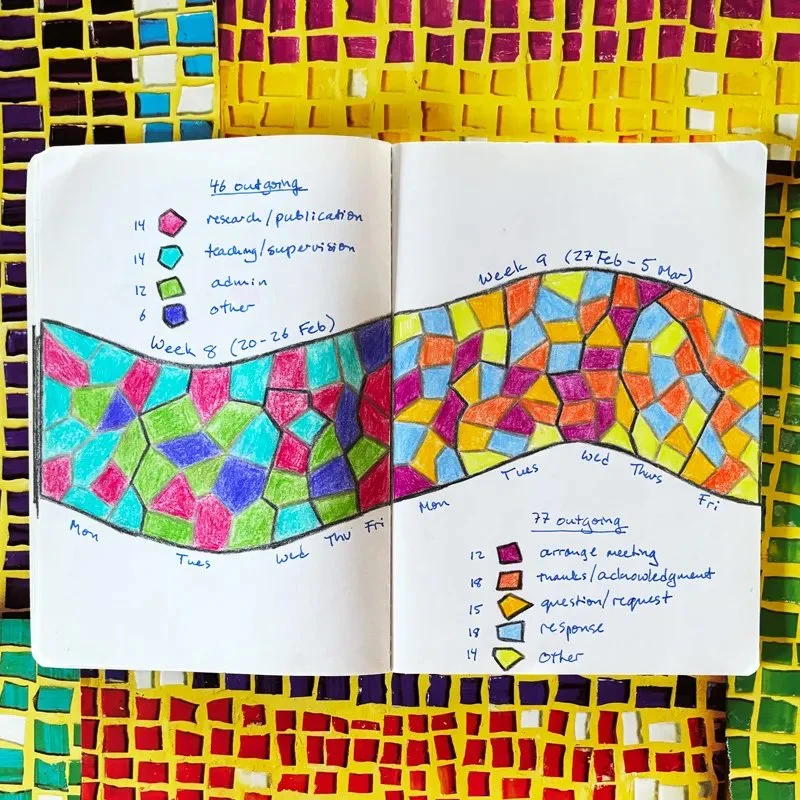

Taking a page from my own Day 26 prompt, “Write in color,” I’ve used colored pencils to spotlight some of the stylistic features in Steve’s work that I find worth savoring.

Enjoy!

The first paragraph

The starting point for becoming a good writer is to be a good reader. Writers acquire their technique by spotting, savoring, and reverse-engineering examples of good prose.

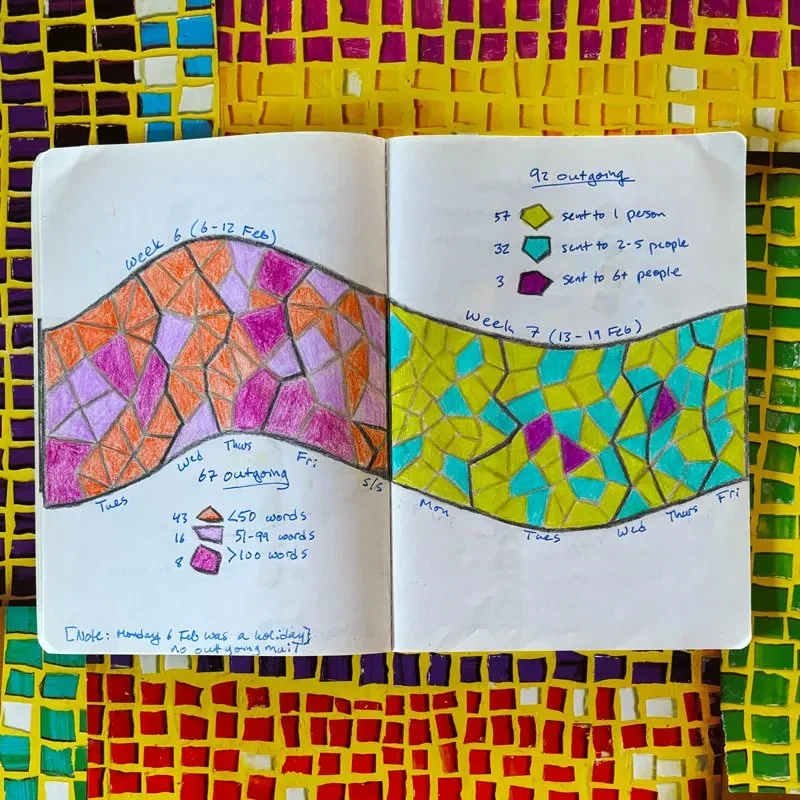

Steve’s opening paragraph (like the sentence I am writing right now) makes two potentially risky grammatical moves: the first sentence contains the bland be-verb phrase “is to be” (highlighted yellow), and we find multiple -ing words (highlighted blue) across the two sentences. There’s nothing intrinsically wrong with either choice. However, as a general rule, be-verbs lack the kinetic energy of more active, vivid verbs, while the suffix -ing can signal the presence of either a verb, noun, or adjective, depending on context; so unless you’re in full control of your syntax, a surfeit of -ings can end up messing with your reader’s brain!

Needless to say, Steven Pinker is in full control of his syntax and style. The is to be phrase in the first sentence functions as a kind of syntactical fulcrum, balancing the phrases a good writer and a good reader (highlighted in pink), while the second sentence uses the repeated -ings to good effect and leaves us in no doubt of Steve’s facility with active verbs (highlighted in orange): acquire, spot, savor, reverse-engineer.

Take a moment, too, to spot and savor the poetry in this passage: the alliteration of spotting and savoring; the assonance and consonance of reverse-engineering examples.

The second paragraph

Much advice on style is stern and censorious. A recent bestseller advocated “zero tolerance” for errors and brandished the words horror, satanic, ghastly, and plummeting standards on its first page. The classic style manuals, written by starchy Englishmen and rock-ribbed Yankees, try to take all the fun out of writing, grimly adjuring the writer to avoid offbeat words, figures of speech, and playful alliteration. A famous piece of advice from this school crosses the line from the grim to the infanticidal:

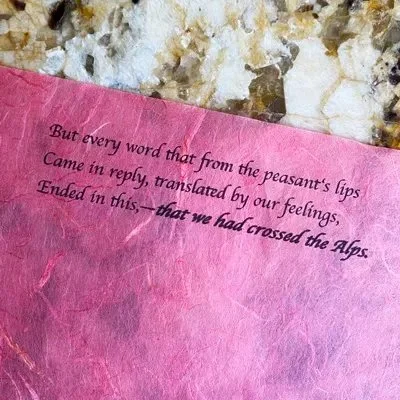

Whenever you feel an impulse to perpetrate a piece of exceptionally fine writing, obey it—wholeheartedly—and delete it before sending your manuscript to press. Murder your darlings.

Moving a bit more quickly now, let’s ride the wave of these four splendid sentences, which roll us inexorably toward that famous “murder your darlings” quote by Arthur Quiller-Couch, a starchy Englishman if ever there was one. To fully appreciate their tidal flow — surging from 8 words to 22 and then 34 before ebbing back to 17 — I recommend that you read the whole paragraph out loud.

Here I’ve highlighted the verbs in orange, the adjectives and adverbs in yellow, the nouns in turquoise, and the colorful quotations from Lynne Truss (Eats, Shoots & Leaves: The Zero Tolerance Approach to Punctuation) and Quiller-Couch (On Style, 1914) in purple.

You can see at a glance how carefully Steve has chosen and balanced every word and phrase — even (or especially?) the ones borrowed from other writers as negative examples.

The third paragraph

An aspiring writer could be forgiven for thinking that learning to write is like negotiating an obstacle course in boot camp, with a sergeant barking at you for every errant footfall. Why not think of writing as a form of pleasurable mastery instead, like cooking or photography? Perfecting the craft is a lifelong calling, and mistakes are part of the game.

Now the floodgates have opened, and the metaphors (highlighted in turquoise) come pouring in thick and fast. We’re carried through the bleak dystopian world of the first sentence, where learning to write resembles a particularly nasty kind of boot camp, to the utopian promise of the second, which offers us a vision of writing as “a form of pleasurable mastery instead, like cooking or photography.” By the final sentence, the word writing has disappeared, transmuted into a craft, a calling, and a game. (The maroon highlighting tracks the journey of writing from learning to doing to perfecting; the orange highlighting illuminates the key phrase at the heart of the paragraph).

Note the quickening rhythm as we’re drawn through the interminable obstacle course of the first sentence (30 words) and the questioning possibilities of the second (16 words) to the punchy promise of the third (15 words). A parallel shift in tone — from negative to hopeful to positive — can be tracked through the transition from third person (“an aspiring writer”) to second person (“barking at you”). By the time we reach the end of the passage, we know that the author isn’t just talking about writing; he’s talking to us.

The list

Though the quest for improvement may be informed by lessons and honed by practice, it must first be kindled by a delight in the best work of the masters and a desire to approach their excellence. Reverse-engineering good prose is the key to developing a writerly ear. Stylish writers, you’ll find, typically share a number of practices, including:

• an insistence on fresh wording and concrete imagery over familiar verbiage and abstract summary;

• an attention to the readers’ vantage point and the target of their gaze;

• the judicious placement of an uncommon word or idiom against a backdrop of simple nouns and verbs;

• the use of parallel syntax;

• the occasional planned surprise;

• the presentation of a telling detail that obviates an explicit pronouncement;

• the use of meter and sound that resonate with the meaning and mood.

Good writing, Steve suggests here, is “kindled by delight.” In that spirit, I couldn’t resist using a rainbow of colors to highlight all the items on his list of stylish practices, as his own writing exemplifies every single one of them.

Thank you, Steve, for the examples and inspiration!

If you enjoyed this post, I highly recommend that you to read Steven Pinker’s book, The Sense of Style: The Thinking Person's Guide to Writing in the 21st Century, from which his #AcWriMoments prompt was adapted.

This post was originally published on my free Substack newsletter, Helen’s Word. Subscribe here to access my full Substack archive and get weekly writing-related news and inspiration delivered straight to your inbox.

WriteSPACE members enjoy a complimentary subscription to Helen’s Word as part of their membership, which costs just USD $12.50 per month on the annual plan. Not a member? Sign up now for a free 30-day trial!